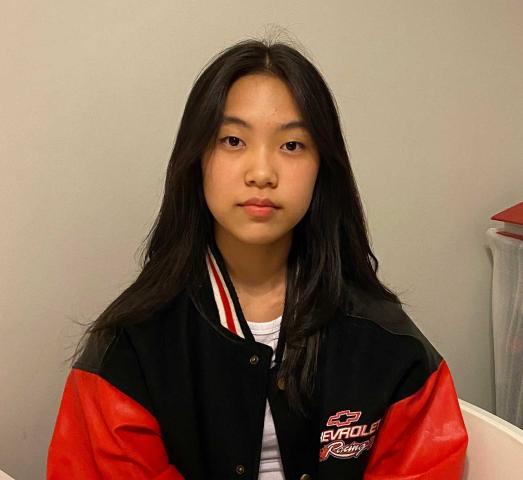

Sarah Yang writes her own coming-of-age story, wrestling with racism, identity, and intergenerational culture clash.

Sarah Yang is a 16 year old who was a participant in an Indigenous-Racialized Youth Retreat in September 2022, that was connected to the 40 Days of Engagement on Anti-Racism. Using an interview format, she shared her experiences of racial discrimination from the lens of a bi-cultural youth growing up in Canada.

How has growing up in a Canadian environment affected your relationship with your parents and understanding of your ethnocultural heritage?

Growing up in Canada, I often clashed with my immigrant parents and our Korean culture. I would bring home Western thoughts and ideas to our family, and yammering in English as my parents tried to listen haphazardly. At other times, my parents spoke to each other in Korean, while I pretended to understand. It was grown-up talk, foreign talk, an inside joke that I wasn’t in on, and a language I had trouble understanding. Soon enough, silence as well as one-word replies served as our shared form of communication. Our differences in culture clashed and I initially experienced a disconnect from my Korean culture.

Already, I felt my appearance did not belong in the Western world and this disconnect strengthened the feeling that I did not belong anywhere, even with those that shared my facial features. This internal conflict manifested in my interactions with my parents. I became angry when I couldn’t understand their culture and upbringing. It was my culture too after all. Instead of addressing the miscommunication and conflict at hand, however, I became passive-aggressive. As a result, words and actions were constantly misinterpreted in my household.

The Joy Luck Club was a book, later made into a movie, that focused on the relationships between Chinese-American children and their parents who had immigrated from China. The movie was able to depict Amy Tan’s experience as an acculturated child, as well as mine, resonating, with my relationship with my mother, and my ties with my Korean culture.

In this book, misinterpretation of culture led to multiple frustrations within the mother-daughter relationships. These frustrations were felt in my family as well, and they and weakened my ties to my Korean culture. With passing time, as I got older and more insightful, this need to be fluent in both cultures has stayed with me. However, I now realize the love from my parents that I once did not completely understand— I now realize the complexity of culture, as well as the importance of communication as an acculturated child.

How does your understanding of racism affect your views on the western media you grew up on?

At the age of 10, I was a stereotypical East Asian child with monolids, slanted eyes, dark coarse hair, and crooked teeth. Regardless, I made it my goal to achieve the a more Western teenage contemporary “coming-of-age” love story when I reached high school. I planned to fall in love with the captain of the football team, become popular, and excel at school.

Now, I am three years into this snake-pit inferno and I have yet to experience any of my fifth grade fantasy. I had learned that fantasy mainly from the media I consumed at 10 years of age, and it formed my formative years and goals. It was only when I entered high school that I realized these coming-of-age goals were flawed for any young person of any identity. But it was particularly flawed for racialized youth.

Though I did not think I was unattractive, I interpreted mainstream media as saying otherwise. The teenage coming-of-age genre originated from the Western canon. It’s oversaturated with White adolescence, disregarding racialized youth and our realities in the Western world. I realized that though this media was not originally created for me, it was constantly shown to me in the mainstream.

The lack of diverse representation in characters and story arcs in television influenced how I thought my growing up should or would be like, distorting the reality I was living in. Like many other girls, I romanticized fitting into the typical coming-of-age teenage archetype and in the process, I imagined a black-and-white image about what girlhood should be like. This was not only harmful for my psyche, but my small community of racialized youth as well. In a way, I started to resent my Korean identity.

Recently, I have found Western pop-culture has witnessed the rise of K-pop (Korean popular music) and anime, polarizing the treatment I have been receiving. I used to be made fun of for my Korean features and culture; yet, parts of it are now being celebrated in the mainstream media. East Asian cultures (Japanese, Korean and Chinese) have become glamourized or fetishized, whereas the rest of Asia was disproportionately looked down upon or forgotten. This makes the continent of Asia seem monolithic, affecting my interactions and relationships with other Asian-descent as well.

I have realized that it is difficult to escape White supremacy in Western pop culture and that Western capitalism can negatively affect racialized communities.

What are your personal experiences with racism?

Since my elementary years, peers and teachers perpetuated racism at every school I attended. Microaggressions heavily contributed to my culmination of hurt and anger. Other forms of racism were blatant as people commented on my facial features, hollered slurs, and assumed Asian stereotypes. I experienced this prejudice from multiple cultures. Much of the racism I experienced was due to a lack of education that heavily impacted my daily living and how I perceived myself. I internalized this ignorance and began inflicting lateral violence within my Korean and greater pan-Asian community. It became common for myself and other students of Asian-descent at school to call each other names and perpetuate cultural stereotypes and bias.

Instead of facing our vulnerability, it was simpler and easier to displace our hurt and turn to crude humour as jokes. A form of saving-face that many of us were unconsciously taught to do when we were young. Morbidly, this internalized racism served as an unspoken but mutual bonding experience between us all. I felt a sense of belonging and solidarity. However, this confidence and feeling of solidarity did not last long. It was fleeting and temporary— the result of avoiding the main issue.

Though I do not displace my hurt anymore, this racism I experienced when I was younger has stuck with me to this day, affecting my self-image and sense of identity.

How do you hope racism is handled in the future? How can we promote a better future for all people?

Although this is an idealistic response, with many more factors at play, I am optimistic that with education and seeking out marginalized perspectives, we can learn to treat each other equitably. With an increased learning about diversity, colonialism, racism, as well as intersectionality we can entail an empathetic, equitable and intercultural future. We must challenge our implicit biases and the way we think about other cultures as well as marginalized communities. With more resources, workshops, and a sense of compassion I hope we can all become more aware of our actions, thinking, and realize the intercultural way.

Individually, I wish to see racism from a different perspective or lens. Before coming to a conclusion when encountering a racist situation, I now ask myself:

- What is their intent?

- Was it curiosity? Malicious?

- How does their intent impact my racialized identity?

In this way, I hope to refrain from internalizing my oppression and associating it with my self-image.

— Sarah Yang is a high school student from Winnipeg, Manitoba. She plans to pursue a post-secondary education after high school. Sarah is affiliated with Teulon and Balmoral United Church Pastoral Charge and has been active in promoting anti-racism. She participated in the United Church Indigenous-Racialized Youth Retreat last fall. She also enjoys reading, crossword puzzles, and exploring her creative nature.

Matthew Tyhurst, a grade 10 student who is White, has written a blog post, "A White Teenager's Perspective on Racism," engaging with Sarah Yang’s testimony, which we invite you to read.

Both Sarah and Matthew are involved with AR4YT, a United Church of Canada anti-racism app geared toward youth, covering topics like the history of racism in Canada, White privilege, and how to get involved in anti-racism work. It is available on Google Play and the App Store.

The views contained within these blogs are personal and do not necessarily reflect those of The United Church of Canada.