Rev. Shelley Pick asks, “What is neurodiversity, how is it related to brain injury, and what should communities of faith know about it?”

I was ordained in The United Church of Canada in 2001 and had special interest in Mission & Service, as well as the Emerging Spirit Program, which was launched to create congregational hospitality toward 30-45 year olds in particular. Not even four years into my second placement, I hit a patch of black ice on my way to work. I sustained a significant brain injury at that time, which was undiagnosed for three years.

This was a time of confusion. I healed from the physical injuries but was hypervigilant and unable to rest or sleep. The myriad of strange symptoms included a lack of physical triggers – I lost my ability to feel hungry or thirsty, and the ability to feel time passing – sitting in silence for hours, unaware. My capacity to sustain thinking and physical activity, as well as 40 years of honing my self awareness, were taken in the blink of an eye.

Listen, I will tell you a mystery! We will not all die, but we will all be changed, in a moment, in the twinkling of an eye, at the last trumpet. For the trumpet will sound, and the dead will be raised imperishable, and we will be changed. – 1 Cor. 15:51-52

“Brain injury can happen anytime, anywhere, to anyone. In a moment, a life is changed forever.” – Braininjuryns.com

There is my life before the accident and my life after. The accident changed who I was. I looked the same, but I was completely different. It was a huge challenge to figure out the way forward. It was much easier to succumb to the negativity and hopelessness. How could I fulfil my call to ministry when I couldn’t even complete the most basic activities of living like sleeping, being around other people, or any type of routine?

I thank God everyday for the skills I learned as a minister, as it was essential for my survival. I knew I needed to concentrate on what I could still do, but knowing something, and doing something are two separate things! I felt completely alone and that no one understood what I was experiencing. When I finally met other survivors through the Brain Injury Association of Nova Scotia, I started to realize the huge group of individuals largely suffering in silence and feeling completely misunderstood. Every brain is unique and therefore, every brain injury is completely different, which complicates everything.

There were very few supports for living with a brain injury or resources at that time, and unfortunately this is slow to change. The next five years finally ended in my understanding that I was now considered “disabled.” When I had any extra energy or capacity, I fulfilled my call to ministry through volunteering with the Brain Injury Association of Nova Scotia.

My former work developing a theology of hospitality with congregations has led me to a passionate understanding of how we unknowingly exclude so many who are brain injured in our society. The United Church is now using the term neurodiversity.

Neurodiversity is the natural uniqueness of human brains and minds. All brains work differently. Neurodiversity means that the human brain processes, learns, and/or behaves differently from what is considered "typical," and this can be genetic or produced by traumatic experiences like the effects of a traumatic brain injury.

In Nova Scotia alone, it is estimated that there are over 70,000 people living with brain injuries. That means there are 13,000 new brain injuries per year, and of those, 3,000 have long term effects. (https://braininjuryns.com)

When there are long-term effects, it means losses, and learning to cope everyday. Ambiguous loss is an unclear loss that defies closure. I have developed a workshop on ambiguous loss, as well as spirituality after brain injury.” These workshops are well attended by brain injury survivors as well as their families, caregivers (if they have any), and professionals.

What should communities of faith understand or do about this?

We all know there is a lot of need out there. In my opinion, many brain injury survivors are suffering silently. Their issues are not understood or even talked about in our society. Traditional programming, services, and community building within churches may not work for these survivors. We brain injury survivors are neurodiverse and, therefore, working with us can not be a "one size fits all" approach.

We are not easy to deal with, as our symptoms are extremely diverse – as diverse as our brains are. There are a few things that could be done:

- Educate yourself on some of the more common symptoms.

- Ask them what might work for them. Instead of assuming their needs like lowering the lighting or decreasing the sound in an event, better yet ask “How can we include you?”

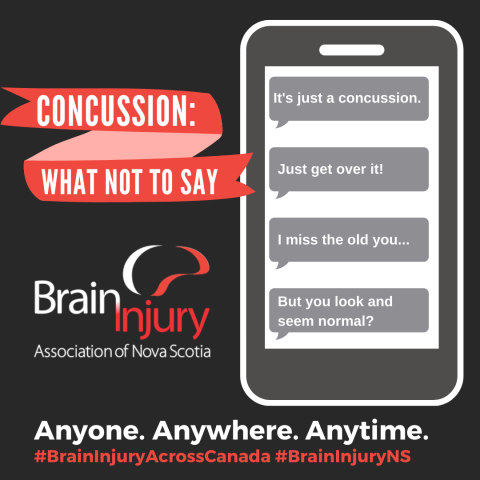

- Believe them – I know that sounds too simple, but many survivors report feeling dismissed, and their suffering trivialized when people respond with: “Oh, I get confused too, I just use my calendar now," or "Yes, my eyes do weird things too," or "Yes, I had a really hard time getting out of bed too," or "Yes, I have a hard time finding the right words.”

- What would be more helpful is a deep listening, and perhaps, “Tell me more about that.”

- What can be annoying and inconvenient for many is like comparing intramural sports to the NFL. Survivors of brain injury are not simply inconvenienced, but live 24/7 with their issues for the rest of their lives. Stephen Covey in his famous book The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People says in Habit 5: Seek first to understand, then to be understood. This habit would help in many areas of our communities and our societies but is particularly needed with brain injury survivors.

I believe it is very important for communities of faith to offer understanding and support for each individual’s unique mind and experience.

– The Rev. Shelley Pick is a volunteer chaplain and community educator with Brain Injury Nova Scotia. She has lived with a brain injury since 2007 and feels passionately about helping brain injury survivors understand and navigate their lives post injury.

Find out more:

The views contained within these blogs are personal and do not necessarily reflect those of The United Church of Canada.